Can you culturally-appropriate yourself?

My family's background always has been under investigation, but now it's under a microscope.

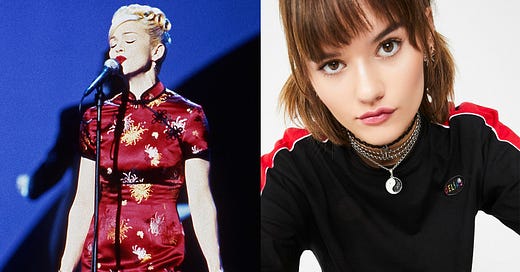

I distinctly remember the time in the late 90’s where it became cool to wear yin-yang necklaces and chopsticks through buns. The high neck, fitted silk style of the cheongsam/qipao dress was suddenly in popular culture. The dresses and hairstyles I usually saw on my aunts and grandmothers were now splashed across Delia’s catalogs and Madonna.

Back then, there was neither language to express frustration nor a willing audience to listen. The mostly white and more popular student body were pulling off these styles to “critical acclaim,” (re: nods of approval at recess), while I was trying to unstick the nickname bok choy from my eighth grade persona because I brought leftover lo mein for lunch — once.

But look at us now! The internet has provided an amphitheater for professional finger wagging, and I (or we) finally feel some sort of protection against these unfair appropriations of culture.

So why do I still feel like something is off?

Well, those who know me might have an idea. Although my father is Chinese, my mother is Irish/South African white.

Before I dive into what I think, this article from Allure from 2017, provides context. It’s a wave in this hurricane awakening of culture-reclamation we find ourselves in today. Part-way through, the journalist starts listing problematic styles — many to which I agree procure that same icky feeling as when Madonna started wearing bindis on the reg.

But then we get to a dress designed by Alexa Chung. In reference to Chung’s “mandarin collar dress,” the author writes:

“OK, Alexa Chung actually is part Asian, that fraction of which gives her a Chinese surname but otherwise the privilege of a white-passing appearance. Things get tricky with race and the politics of passing, and there is absolutely no questioning that Alexa Chung is "Asian enough" — in fact, if there was anyone who could single-handedly make a mandarin collar come back with a vengeance it would be her. But the irksome bit then is: Why not use a Chinese model? Rich white girls will still buy it, don't worry (the eponymous line falls under what I'd call Luxury Bish price point).”

Reading this was a rollercoaster. It began with so much YES and then when I arrived at the above passage, it felt like someone was escorting me out of a private party after finding out I used a fake ID.

Chung was being weighed in the balance; an invisible, but palpable checklist was formed to see if her looks and heritage are “enough” to render that dress “correct.” “That fraction,” of her surname helps her in this case — I wonder if my married name of McCracken would have had me down a level if I were on trial. Is there anything more devaluing than having your name chopped down into mathematical measurements?

Sure, Chung finally passes her test but the author was frustrated that an Asian woman wasn’t the model. I won’t say it wouldn’t have been great to see that, but did we all think that Chung was only marketing to Chinese women? Or half-Chinese? Would my daughter who will be 1/4 Chinese be allowed to buy this dress one day? Would she be allowed to model it? How can she or the retailer measure that? The dress was widely available in department stores like Selfridges and online to everyone. Models should be chosen at the creative director’s discretion. Naive? Sure. But we need to hold onto hope that more directors will hire more diverse models. The backlash method that comes from social media trolling only creates anger and hiring out of spite. Representation can’t have the same effect if we’re all scanning the internet judging what is correct by guessing where people come from based on their looks.

Cousins: Holding my baby sister, next to my brother in the center, second from left.

Being half-white and half-Asian has made me in a tug-of-war for identity since birth: People asked if my mother was my nanny. Friends told me to wear eye-liner a certain way to make me look less Asian. Chinese friends didn’t invite me to their Chinese mall hangs because I couldn’t speak the language. My face is too Chinese to be a model, but I could try radio because I don’t have an accent. Since I can remember other people have been telling me where to put parts of my physical and mental body. My skin, my liver, my eyes, my brain; fractioned again and again. As if people couldn’t carry the weight of my wholeness, I needed to be cut up to fit in.

So, what if then, my father brought me home a silk dress from Chinatown? Should I cover any white parts of my body to wear it? My parents always said I inherited my mother’s large Irish feet, shall I cut them off when I slip into my qipao? When I was little I was told I look more Chinese then than I do now — should I start tossing away anything Chinese in my closet because my white-passing features are becoming more prominent? Will journalists start measuring the angles of my eyes and the amount of red I flush when I drink? And then, when all is said and done, how many more years of Chinese-passing kids do I have left in my body before they’re simply not allowed to wear what mom and mom’s grandmother wore/ate/cooked. Yes, pushing this to the extreme here, but these snarky questions are a result of being left out of the conversation. When it comes to flipping the script on culture hierarchies, the mixed typically stay in the middle, suspended.

My sister was born six years after me with bright blonde hair and green eyes. She’s my mother and father’s daughter — something private I hate that I have to state so openly. We’ve been at dinner parties before, introduced ourselves as sisters while the host followed up with, verbatim, “That’s not how genes work.”

My brother, me, and my sister at my wedding in 2016

The author from the Allure article writes:

The way that white girls are “wearing fashion kimonos flung loosely around them as outerwear, but purporting the image of such is alienating and disrespectful to the people whose culture you are taking from.”

Yes, if your family is a seventh generation Acadian-Mainer, and never cared to read about Japan let alone have any connection, it feels off to traipse around town in a kimono. But in this particular sense, I can’t help but think of: “the people whose culture you are taking from” — which people are you referring to? Because I can only really read that as people with Chinese parents on both sides. And maybe that is her intention. I guess I’m confused. At first I wish it was more plainly stated, but then I know, it can’t ever be.

My dad, me, my daughter, and my sister in 2020.

When my daughter grows up, she will have to unravel a history that is mixed with all of me, plus Dutch and American blood. We try to navigate that territory with awareness. When I suggested an Irish name for her, my husband pointed out that it might be too removed to get away with calling her Siobhan. As much as that made my skin hot I could see the teasing now. I get it all the time when I tell people I’m Irish.

But how many generations removed from Ireland can white Americans name their kids Finnegan or Saorsie without getting so much of a second glance, when my grandmother was from Ireland? I can bet all my money it’s because in that case I’m not white-passing enough.

As I hope we’re all learning, these issues aren’t “divided in two,” or black and white. They are as multi-faceted as my family tree. I can and would passionately advocate that the Cleveland Indians change their name and be all for a restaurant that serves both Chinese and Irish food. It might seem obvious these two things are not mutually exclusive, but in many heated conversations I don’t find that the case.

There’s a history of the oppressed we should all do our best to educate ourselves on, and yes, recognize when things aren’t appropriate. I am not ignorant to the benefits of having white-passing features. It’s something I’m dedicating my life to study. For the first half of my life, all I wanted was to bury my “non-white” self. I don’t feel the same way anymore and I do wonder if I can live the rest of my life free from the indoctrination that shaped me. Knowing that, there still doesn’t seem to be space for people like me, in many discussions surrounding cultural-appropriation.

People of cultures around the world revere time-honored traditions, but for some reason our modern day mixed-kids have a shelf life on what we can call ritual or not. I can only conclude if you’re “purely” one race for generations you can hold onto your garb and ceremony, but the second you’re mixed with many, the value of each of our culture’s markers rapidly diminishes.

I think of my sister, who technically has attended more Chinese family dinners, dim sums, and family trips than me, on account of still living in her home city. Yet many might discredit her connection to those roots because of how she looks. To many, her features lend her privilege, but can anyone advocate for the culture she’s lost?

I love your style of writing and your insight . I particularly love the photo of you and your wonderful siblings. Much love , your elementary teacher

Coco, your words are Power. You are exquisite.