Portrait by E. Julien Coyne

I was not interested in my ancestry until recently. Like some friends my age, we agree this is unfortunate timing; having living grandparents would make the detective work much easier.

When my husband, Ian, first met my Chinese family at a rowdy dim sum spot in Markham, he asked me what part of China I was from. I was 22 and did not have an answer. Ian turned to my Aunt Ping, and she answered him. I don’t remember what she told him.

What I did know was that we didn’t speak Cantonese or Mandarin but another dialect that came from Taishun County. In sentences murmured with the telltale Canadian question mark at the end — it went something like: We come from Guangzhou? We speak Tai Shun?

A quick Google search makes this more confusing because the distance between these two places is about 1,000km. This is usually where my curiosity ended, and I went back to whatever I was doing before (learning Elvish, researching Renaissance Faires, etc.)

That was until, Ian’s mother entered my story. My mother-in-law, all six-feet of her, sauntered into my life with swinging blonde hair, a New Jersey accent that could also perform perfect Dutch, and a never-ending curiosity about family trees and ancestral lands.

In finding out that my grandmother immigrated to Canada from Ireland, Carole became fixated on getting my “butt over there” — and eventually she made it happen. We traced my grandmother’s exodus, which led us back to her home town of Bangor, Northern Ireland. Once there, Carole suggested we knock on all the neighboring doors and ask after Nanny, as us kids called her (Joan to everyone else.) “Anyone that looks over 60, we should just ask them if they knew her.” I thought that was ridiculous until we met a local jeweler who’s late brother dated my young grandmother.

Some details started to plug into the puzzle of my family history, which I thought would bring me answers. But, as I stand today, I honestly have more questions than ever.

Then, for my birthday this year, Carole bought me a DNA test.

—

The biggest question mark I have in my family comes from Joan’s life. The grandmother I was closest with, remains the most mysterious to me.

Plainly put, my grandmother did not know who her parents were. To add more pages to this blank book, her first husband, my grandfather, never met me. (He didn’t speak to my mom in the years leading up to his death.) I know barely a thing about him except that he was born in Johannesburg, South Africa, and he was an architect.

Anytime we’d make a family tree in school, mine looked like lightning struck it. A plethora of Yips, Chengs, and Lais sprouting from every branch on the left, and a light sprinkling of McNeillys and “____?”s on the other.

—

6-8 weeks after willingly spitting into a tube and sending my body’s code to a private corporation, I got my results back and:

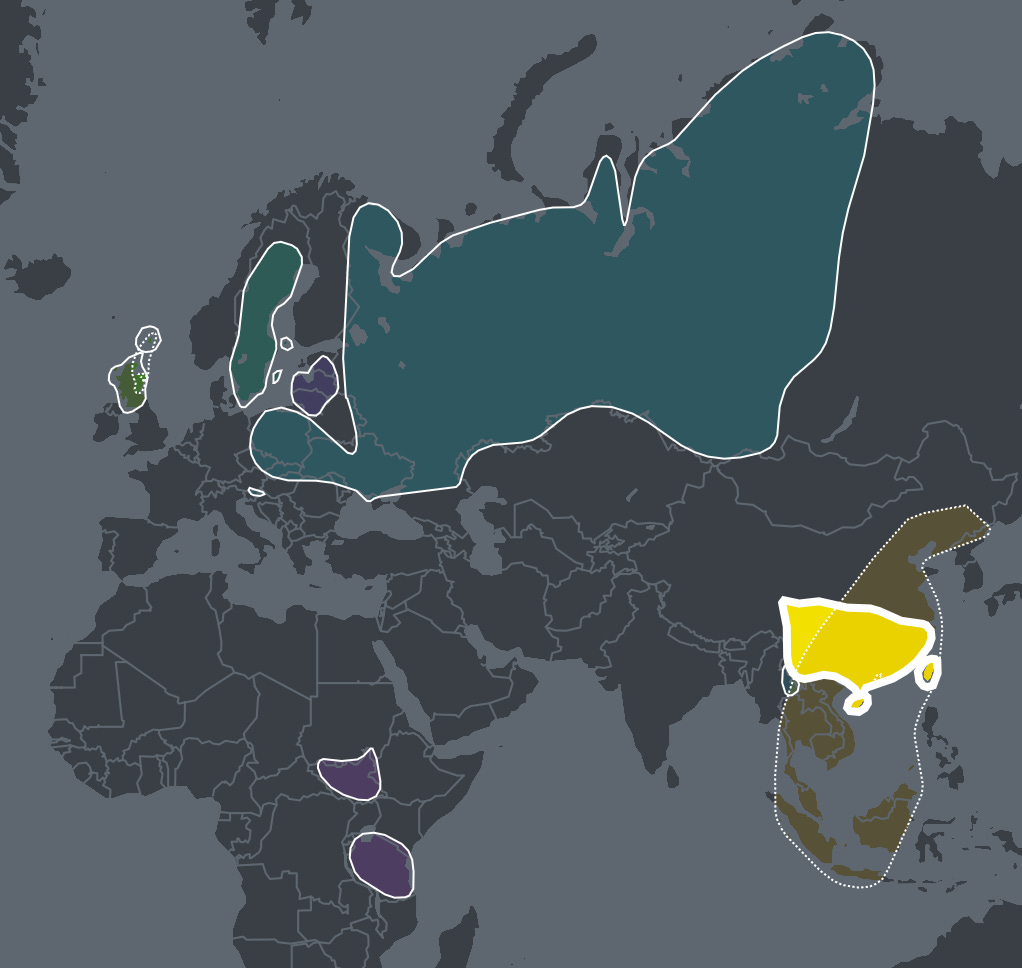

Southern China (Guangzhou) 48%

Scotland (Northern Isles) 37%

Sweden 6%

Eastern Europe/Russia 3%

Dai 3%

Baltics 2%

Khoisan, Aka, Mbuti Peoples 1%

—

I’m not sure where to go from here. My life narrative has always been “half-Chinese, half-Irish,” which is close enough to what this map outlines. But seeing “what you are” written in percentages makes me feel like I’m pressing uncomfortably hard against my life mantra — Which is, in so many words: Stop f*cking asking me where I’m really from.

This is to ask: should I feel less interested in the 1% of me that might be Mbuti, rather than the 6% of me that’s possibly from Sweden? If we’re going to really split hairs, do all the boxes I need to check on forms have to be Asian now, since I’m 11% more Chinese than Scottish/Caucasian?

I can’t help but think of our families and communities before the industrial revolution, and how a connection to land and place came with storytelling, adorned cloth, and the social circles within those borders. How many stories will I have to learn and re-tell of my South-African grandfather before I am donned South African enough — or does this science experiment strip that honor away from me now since it’s barely on the map?

I never identified as Scottish in my life. But now I keep thinking of my first trip to Edinburgh as a teenager. I wonder if my attraction to the city had something to do with my ancestors sending me messages from beyond the cobblestone, or was it just the first time I enjoyed Smirnoff Ice without getting carded?

Of course, the piece that arcs above all of this is the simple fact that I was born in Canada, and I am Canadian (cue kinda cringey Molson commercial here). But I rarely say, “I’m Canadian,” to those that ask where I am from. (Also because I know that never satiates their true question of “why do you look like that?”)

I would be curious to see how many kids in the US and Canada complete these ancestry tests versus people in Peru, Iran, Cambodia, Mexico. Are we curious about where we came from because our parents and grandparents had the privilege of a successful* immigration? Why do children of first world countries get so excited to find out they’re from second or third worlds? The cynic in me might theorize that we’re bored of who we’ve assimilated into, we’re clutching onto any narrative that extends beyond our first Instagram post.

But, a less-pessimistic part of me sees a crack in my drywall, perhaps a hole that was hastily pasted over, with intention to be found again. Over the past decade, I’ve spent more time than ever deciphering not just where I am from, but why I am from. I have Carole to thank for that.

So here I am with more questions than answers. Kind of a nightmare situation for someone trying to write a memoir who’s searching for material to cut away.

Maybe it’s this new-found treasure map that scares me more than anything. What will I find if I keep looking? How are these ancestors connected to any current living relatives I haven’t met yet? What kinds of illness or proclivities do I have in me, from them?

I guess my first lesson should really be, ask my Aunt about China again, and this time, write it down.

Too good. Love this.